For a little while now, I’ve been thinking about all that a recipe can hold. The list begins with nurture and nourishment. Then, helpful instruction, but ideally also some space to experiment. Memory, memoir, and the potential to deepen someone’s connection to their roots. An invitation to create and collaborate. Inspiration, pleasure and care. Maybe frustration, too. A pathway towards cultivating a distinct appetite. The opportunity to share and affirm or refute another cook’s tastes. Satiation of wants and needs. A method for bringing a loved one joy. Sustenance. A demarcation of time well spent – feeding and exploring and living. Everyday magic.

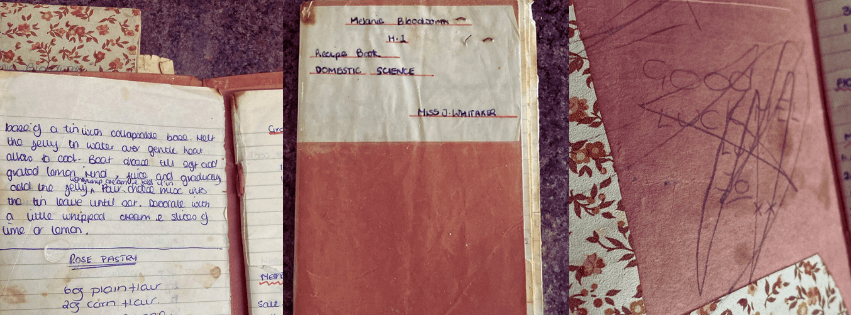

I’m interested in the relationship between recipes and time. As a child, I saw old recipes as time capsules. Mum’s Domestic Science cookbook wasn’t simply a keepsake from her school days, but instead a portal to the world before I existed. The cover resembles one of those Squashies sweets, part white, part pinky-red, but instead of uniform smoothness, the paper is crinkly and imperfect all over. She wrote her name front and centre in characterful blue ink, then precisely underlined it in coral. Her handwriting is immaculately neat; the book itself is much-worn with age. The inside edges are reinforced with thicker card, a brown floral border thoroughly glued and stapled down. It looks like it was done in haste – the back cover has pulled away from the spine nonetheless. Another hand pencilled in an impromptu inscription, “GOOD LUCK MEL LOVE JO XX”, in noisy block capitals. There is a scribble on top of this message – an embellishment I seemingly couldn’t resist adding at some point over the years. It’s a tiny palimpsest of our younger selves.

Throughout my childhood, the recipe we revisited the most from Mum’s book was a gloriously seventies concoction – lemon and lime cheesecake. We rarely had sweets at home, so the emerald cubes of jelly we’d dilute to prepare the dessert’s jiggly topping felt like an extraordinary and mischievous treat. I’d read out the ingredients in ounces and eighths of pints and measure out the quantities with old-fashioned iron scales, placing down and picking up little golden weights until the two sides stopped rocking and found stillness. We’d crush ginger biscuits and melt butter and Mum would tell me of how in her exam she was afraid an invigilator would interpret her friend’s note as a secret code and accuse the two of them of cheating. She was convinced the cheesecake would refuse to set, but she persevered, improvised an extra step of putting it in the freezer and at the last minute, it all came together better than she could have hoped. Sometimes things just aren’t worth worrying about. Sometimes things just work out in the end. Holding the book again now, I notice a small char in the top left corner. I wonder if Mum did that, or me.

I’m drawn to recipes for their insistence on slowness, on taking time over taking care of yourself and anyone else you feed. Many recipes boast of their speediness, but even those ones stand in resistance to the mindless convenience of just adding water to a “nutritionally complete” powder. Recipes make no promises of providing contrived relief at the many grams of nondescript greens you have ingested in a matter of seconds. Their aim is never to enable you to consume the nourishment you’ve created as rapidly as possible – they make no commitment to saving time by shirking preparing and consuming an actual meal. Instead, following a recipe demands our concentration and presence, instilling attentiveness to the colours, shapes and textures of the ingredients we grow, purchase, chop, peel and transform. As Rebecca May Johnson writes, “a meal is more than a dish: it is also the period of time during which eating takes place and the sequence and arrangement of things eaten. Eating a meal is an interruption to work through which I can taste fragments of utopia in a tangible form”. Writers document their recipes to offer a hand to hold through what might otherwise be intimidating, overwhelming, or simply a chore, in the hope of extending fragments of utopia beyond their own kitchen. Sharing a recipe is an invitation to savour.

While I’ve been contemplating recipes, I’ve also been reckoning with how to mourn. Grief was a foreign language for most of my life, then gradually its waves began to engulf me over and over again. A week before my husband and I got married, it struck our family with newfound depths of sorrow. It was this sentiment, most beautifully captured by Mary Oliver, that gave us the courage to go ahead with our plans:

We shake with joy, we shake with grief,

what a time they have, these two

housed as they are in the same body.

I am of course far from alone in turning to cooking as a source of relief and resolve in the wake of tragedy. We cook to provide for those we love. Food grounds us and sustains us in more senses than one. As Nina Mingya Powles writes, taste can transport us to “so many places at once, all of them a piece of home.” Recipes afford us the chance to perpetuate the magical, transportative and transformative potential of food, by inviting others to repeat, reinvent and recreate the tastes that inspired the original writer. They are a hopeful antidote to finality.

So, I’d like to write recipes as love letters and tributes to the people I cherish, to devote time to understanding and recording the flavours that bring them delight. And, I’d like to write recipes that give me more time with the loved ones who are gone from my sight, by sharing stories of foods that brought them joy while they were alive. I’d like to make time for creating and cooking and living. Time to savour.

Lemon & Lime Cheesecake – Mum’s version [and my vegan one]:

4 oz digestive biscuits [or 200g Biscoff biscuits]

2 oz butter [or 60g dairy-free butter]

½ lime jelly block [or one sachet of Vege-Gel]

¼ pint water [or ½ pint undiluted lime cordial]

½ lemon’s juice and grated rind

8 oz cream cheese [or 225g dairy-free cream cheese]

⅛ pint whipping cream [or 75ml dairy-free whipping cream]

1 lime or lemon to decorate

Grease a 20cm tin with a collapsible base. Crush the biscuits until they form a fine crumb. Melt the butter, add the biscuits and firmly press into the base of your tin. If using a block of jelly, melt it in water over a gentle heat, then allow this mixture to cool. If you’re making jelly using Vege-Gel, pour the cold, undiluted cordial into a pan, add the sachet of Vege-Gel, stir until completely dissolved, bring to a boil and then allow to cool. Beat the cream cheese until soft, add the grated lemon rind and juice, then gradually incorporate the jelly. Beat the whipping cream until soft and add this to the jelly and cream cheese mixture. Pour this mixture into the tin and leave in the fridge to set. Decorate with some more whipped cream and slices of lime or lemon.